Teens & Money - Talking to teens about money (English)

This 21-page booklet is designed primarily for parents but may also be useful for older teens. It covers many topics, including working, budgeting, figuring out if a purchase is a "need" or a "want," banking, writing checks, savings, credit cards, credit reports, driving and cell phones. The booklet contains illustrations and examples of a weekly spending evaluation, a paycheck stub, how comparison shopping can save money and how to write a check. It also contains a list of helpful web sites for parents and kids.

Publication Series

- This publication is part of the Teens and Money training module.

Download File

PDF files may contain outdated links.

Teens & Money - Talking to teens about money (English)

File Name: Teens_And_Money_2013_EN.pdf

File Size: 0.3MB

Languages Available

Table of Contents

Teens and money

Building your teen’s money skills

From a parent’s perspective, it’s just a few short years from lemonade stands to college credit card come-ons. But these transitional years are a perfect time to help your children build sound money management skills.

As parents, you play a key role in shaping your children’s values and attitudes about money management. While you might not think your teen wants to learn these lessons, the Schwab 2011 Teens & Money Survey found that three-quarters of surveyed teens said learning about money management, including budgeting, saving and investing, is one of their top priorities.

The pressure’s on

Very few young people want to be dependent on their parents as adults. Even fewer want to find themselves deep in debt. But there are many pressures in today’s society that cause people to get in financial trouble.

Teens—always under pressure to conform with their peers—also must contend with high-pressure marketing.

Only a strong role model can begin to counteract teen peer pressure. Talk to your kids about money on an adult level. Introduce them to the concept of providing for their basic needs (food, clothing, shelter, education and transportation) and setting priorities on what they want to buy. Life is about realistic choices. Explain that a Porsche is cool, but a dependable used car will get you to school and work just fine, even if your friends tease you about driving a “junker.”

If your neighbor gets a new car, do you want one, too? Such behavior used to be called “Keeping up with the Joneses.” Now the phrase “affluenza” is used to denote money problems such as overspending, misuse of credit and falling into debt. Unfortunately, affluenza can be contagious—your children learn from you. If you’re a shop-a-holic, chances are good your kids will be, too.

Sometimes kids want to buy things because of peer pressure, sometimes out of boredom, sometimes just to see if they’ll get their way. Help your kids understand that there is more to life than trips to the mall by looking at your own habits and asking if your actions are sending the wrong messages.

Working

The working life

Having a job helps your kids prepare for adult life. It teaches them responsibility, gives them job experience, puts money in their pockets and keeps them off the streets.

Work habits formed as a teenager follow you the rest of your life. Some kids naturally want to work, others need encouragement. If you have a comfortable income, you might feel it’s not important for your kids to work—but that’s not necessarily best for your child. No parent wants their children to work so much that their grades suffer, but teaching financial responsibility can be difficult if your child doesn’t know what it’s like to earn his or her own money.

Teens 16 and older generally can work full time, although some states may limit the times of day they can work. Teens aged 14 and 15 can work 18 hours a week but no more than three hours on school days. In the summer, they can work 40 hours a week, eight hours a day.

Younger teens can do odd jobs such as running errands, babysitting, dog walking or lawn mowing.

Many teens work to pay for clothes, video games, gas or cell phones but overlook the added benefits of job experience and seeing what adult life is like. Even a fast-food job can give you some transferable skills such as handling money, using a computer system and dealing with customers. No job is a dead end if you know how to market yourself.

Familiarize your kids with job hunting tools. Go over the basics of resume writing—there are many web sites and books on the subject. Gather some job applications from local businesses and review the information they ask for. Read help wanted ads in the local newspaper. Play-acting a call to a potential employer or a job interview can raise your child’s comfort level for the real deal.

Discuss some of the often overlooked traits that please employers, such as neat grooming and dress, politeness, being on time, doing what you’re told, paying attention and asking questions if you don’t understand. Remind your teen that many employers check job applicants’ online presence before making a hiring decision. Manage your social media accounts so that they don’t reveal anything you wouldn’t want a college admissions officer or prospective employer to see.

Urge your teen to start looking for a summer job early, instead of waiting until May or June when positions may be scarce. Rather than just dropping off an application, suggest they ask when the manager has time to meet with them. Many teens want a job they consider cool so they have blinders on when it comes to what’s out there. Brainstorm together about possible jobs—depending on their interests, teens may find jobs as camp counselors, tutors, tour guides, lifeguards, receptionists, landscapers, day care workers, auto mechanics, construction crew members, maintenance workers, sales help and library aides.

Time equals money

Does your child know how long it takes to earn $50 to buy a video game? According to the U.S. Department of Labor, the average annual earnings of executive secretaries and executive administrative assistants was $50,220 in 2012. It would take a person with this salary a little more than two hours to earn the money for the video game.

The incredible shrinking paycheck

Young people who receive their first paycheck are often surprised that their take-home pay is less than they expected. They are expecting the full—or gross—amount of their earnings instead of the after tax—or net—amount.

Federal and state income tax is the largest deduction. Make sure your kids understand that they can avoid withholding too much by claiming additional allowances on the W-4 form they get from their employer. However, they must withhold at least the amount they owed in taxes last year or 90% of what they expect to owe in the current year, whichever is smaller. Let your kids know that they’ll receive a refund of excess withholding when they file their tax returns between January 1 and April 15 of the following year.

Social Security (FICA) and Medicare (MedFICA) taxes are withheld to pay for government retirement and health care benefits for seniors who reach the eligible age. Explain that employees pay one-half of these required taxes and employers pay the other half, and that taxpayers don’t get refunds for these taxes when they file a tax return.

Budgeting

Watch what you spend

A budget is a spending plan to help forecast and control expenses. By watching what you spend and carefully allocating their money, your kids can save to buy things they want but can’t afford at the moment. Most people just can’t go out and buy the things they want without some planning.

A budget is a spending plan to help forecast and control expenses. By watching what you spend and carefully allocating their money, your kids can save to buy things they want but can’t afford at the moment. Most people just can’t go out and buy the things they want without some planning.

A budget doesn’t have to be fancy—keep cash receipts and bills in an envelope and use bank statements to see where the money goes. Planning ahead helps your kids see how much they can spend each month.

Suggest that your teens jot down everything they spend for one week and then evaluate the results using the weekly expense worksheet shown below. After one week, go over the worksheet together. Is the “bottom line” a positive (plus) or negative (minus) figure? Did your child’s income—from an allowance or working—cover the outlays? Are there any areas that can be trimmed? Which of the expenditures are things they need and which are things they want?

Help your kids develop a budget based on the information and insights gained from the worksheet. Then, for the next few weeks, suggest they do weekly spending evaluations to see how well they’re staying within their budgets.

| Weekly spending evaluation | |

Weekly expenses |

|

| Food (lunch, snacks) Public transportation (buses, subway) Car (gas, upkeep, loan payments, insurance) Entertainment (movies, games, magazines, music) Computer (software, hardware, games, DVDs) Communications (cell phone, Internet/data service) Gifts Clothes Savings Other |

________________ ________________ ________________ ________________ ________________ ________________ ________________ ________________ ________________ |

| Total weekly expenses | $ ________________ |

Weekly income |

|

| Allowance Earnings Gifts Other |

|

| Total weekly income | $ ________________ |

How did you do? |

|

| Total weekly income Minus total weekly expenses |

________________ - ________________ |

| The bottom line | $ ________________ |

| What have I learned by tracking my spending? | |

| ______________________________________________________________________ | |

| ______________________________________________________________________ | |

| ______________________________________________________________________ | |

| ______________________________________________________________________ | |

Needs versus wants

Needs and wants

Get your children to think about priorities and stimulate discussion with this simple exercise. Ask them to list five things they need and five things they want but can live without, with a price tag on each one.

Five things you need:

Concentrate on things that you use or require every day—even if your parents usually pay for them. Suggestions: lunch, bus fare, clothes, shoes, grooming products like shampoo, soap and deodorant.

| Five things I need | How much does it cost? |

Five things you want:

In the next spaces, write down things you would love to have but can live without. Suggestions: music downloads or computer games, your favorite snacks or soft drinks, or new designer fashions.

| Five things I want | How much does it cost? |

Now look at the lists in the following ways:

- You have $500. Prioritize what you’d buy from the items on the two lists.

Why did you choose the things you did? Can you think of any way you could stretch the $500 to get more of the things you want? - Your mom loses her job. You have to help pay for your needs. Cross off some things on either list you can do without.

How could you save money on the remaining things? - You are five years older. Would any of the items you want to buy still be useful or valuable to you in five years

How do you think your lists of needs and wants will change when you are five years older? - Your fairy godmother grants you one material wish. Would you choose to have any of the things on your “wants” list?

If you answer no, perhaps the things you wrote down are not really top priorities for you. Would buying them just be a waste of money?

| Are these needs or wants? | ||||

| Is this a need or want? | Why? | Cost | Alternatives | |

| Fast food lunch | want | tastes good | $4.50 | brown bag lunch |

| Shoes | ||||

| Video game | ||||

| Nail polish | ||||

| Belly button piercing | ||||

| Car insurance | ||||

| Prescription eyeglasses | ||||

| Designer shoes | ||||

| Teen People magazine | ||||

| Backpack | ||||

Comparison shopping

The art of shopping

Enlist your kids in preparing a household shopping list. Ask them to come with you to your favorite superstore—it’s a great chance to show them how to comparison shop. The store brand version of a must-have item is often made by the same brand-name manufacturer that advertises on national TV—but it may cost much less.

Comparison shopping can have a big payoff for just a small amount of work—especially if you use the Internet. Online shopping services known as “bots” (www.pricegrabber.com or www.bizrate.com) can help you start the shopping process by allowing you to compare prices on specific goods. Even if you don’t purchase the item you are interested in online, you will be armed with information that can help you make informed purchasing decisions.

People are shopping in droves at flea markets, yard sales, secondhand stores, thrift shops and businesses that sell “gently used” goods on consignment. Take your kids along on the hunt for a good deal—maybe they’ll get bit by the bargain bug when they find some cool vintage clothes or funky furniture for their rooms.

Vintage clothing and “retro” stuff is in, but used cars have something else to recommend them—more quality and even safety for the price. You can get a much better car for your money if you buy a recent model used vehicle instead of a lower-end new model. (See “Gotta have wheels”)

| Shop around and save | ||||

| Using the Internet to compare prices—even if you don’t buy online—can help you be a more informed consumer and know when to bargain if necessary. Among these three items, a savings of up to 55% was found. |

||||

| Product | Low price | High price | Savings | % Saved |

| MP3 Player | $120.69 | $159.71 | $39.02 | 24% |

| CD | $9.89 | $18.98 | $9.09 | 48% |

| Video game | $21.79 | $48.35 | $26.56 | 55% |

Banking

Bankable teens

Checking and savings accounts are great ways to help young people learn to manage money:

- By teaching your kids to manage a checking account, you can also pave the way to good financial habits such as careful money managment, paying bills on time and handling credit cards well.

- A bank account—savings or checking—is handy for cashing paychecks.

- Writing checks is a safe alternative to carrying cash.

- An ATM or debit card, which comes with many checking accounts, can serve as “training wheels” for using credit cards.

ATM fees

ATMs are convenient, but stick to your bank’s ATMs. Using other banks’ ATMs exposes you to hefty fees. According to Bankrate, a free online financial information service, the average fee for using other banks’ ATMs is $2.50 from the owner of the ATM plus $1.57 charged by your own bank. At these prices, one withdrawal per week adds up to more than $200 per year.

Finding a bank account for your teen

In many communities there are banks and credit unions offering special accounts for young people. Avoid accounts with fees, service charges and minimum balance requirements that quickly eat up deposits.

Suggest that your teenager call some banks. Bankrate allows you to find and compare checking and savings accounts by ZIP code or by city. Online bank accounts are listed, too.

Also check out the accounts offered at local credit unions, non-profit financial institutions that are owned and controlled by account holders. Credit unions are founded to serve groups that share something in common, such as where they work, live or go to church. Credit unions generally provide lower-cost checking options than banks.

To find local credit unions that you may be eligible to join, visit aSmarterChoice.org, a directory of the nation's credit unions.

Most youth accounts are “custodial”—an adult must open the account on behalf of the minor and the adult is responsible for the account. When you and your teen go to open a bank account, you’ll both need to bring identification—a driver’s license or a state identification card—and your Social Security numbers. If your teen doesn’t have a Social Security number, contact the Social Security Administration to apply for one.

Special accounts for youth usually require a low minimum balance ($1 to $5). Some banks may limit the number of checks you can write per month. Look for “free” youth accounts that have no minimum age requirement or monthly service fees and offer unlimited check writing with no per-check fees. Some banks offer a slightly higher interest rate for youth accounts.

A costly mistake

Bouncing checks can be very expensive—up to $35 for each bounced check. Stress to your kids that it is important to keep track of checks and ATM withdrawals so that they don’t overdraft their accounts.

Banking wisdom

Explain how to handle a bank account properly. Let your kids know that if they bounce a check and don’t pay it back, their names will show up in a national database called ChexSystems and they won’t be able to open another checking account for five years.

Share these important check-writing tips with your kids:

- Make sure you have enough money in the bank to cover the check.

- Review your bank statements promptly.

- Record all the checks you write in your checkbook register or use duplicate checks that create a carbon copy of each check.

- Deposit paychecks and other checks in a timely manner—most checks cannot be cashed after three months.

- Use a pen—never a pencil—to write checks.

- Write your checks legibly—scribbling can cause problems when the check is cashed.

- Fill in the check amount and payee well to the left to prevent someone from adding numbers to make the check larger or altering the payee's name.

- If you need to correct a mistake on a check, tear up the check, enter it as "void" in your checkbook register and write a new check.

- Don't sign blank checks—they can be stolen or used by someone else.

- Know where your checkbook and ATM card are at all times and report missing checkbooks, checks or cards to your bank immediately.

Writing checks

The right way to write a check

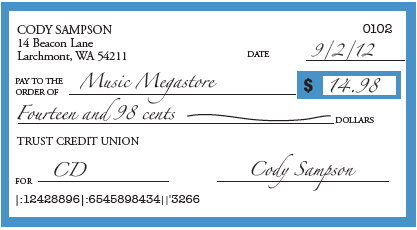

The check below belongs to Cody Sampson. Cody is going to buy a CD at Music Megastore. Follow the directions below to write a check to Music Megastore for $14.98.

1. Date: Write the month, day and year: “Sept. 2, 2012”

2. Pay to the order of: Write “Music Megastore”

3. Amount ($): Write “$14.98”

4. Dollars: Write “Fourteen and 98 cents” and draw a line to fill the rest of the space. (This line is to prevent crooks from altering the amount.)

5. For: Write “CD”

6. Signature: Sign the name “Cody Sampson”

To see what this check should look like when it is filled out properly, refer to the example below.

The balancing act

One of the most important financial lessons is how to balance a checkbook. If you fail to keep an accurate record, you could bounce a check. Bounced check fees from your bank can be up to $35 per check. Most merchants also add an additional penalty of up to $30 on checks returned for lack of funds.

There is a sample check register and some questions to help your children learn about balancing a checkbook. After reviewing the register, your kids should be able to figure out the responses. (The answers can be found upside-down under the check register.)

Questions about the Sample Check Register shown below:

1. What was your balance on July 13? __________________________________

2. How many CDs did you purchase using a check in June?___________________

3. How many checks did you write in July? _______________________________

4. What’s your balance after you wrote a check to Music Megastore on Aug. 6?

___________________________________

5. How often did you use your debit card to make purchases in July?

___________________________________

Saving

Savings add up

| A good way to demonstrate the power of savings is to play with one of the many online calculators. Just type “savings calculator” into an Internet search engine and you come up with dozens of easy-to-use tools. Plug in a few numbers—potential deposits, a realistic interest rate and years to maturity—and you’ll be able to show your teen how regular deposits into a savings account make money grow. Because your teen is coming of age in a time with paltry savings interest rates, it’s tough to demonstrate the power of savings. The important lesson is to save regularly and have a cushion to fall back on if you need it. But even at interest rates of 1%-2%, socking away just $20 per month can build more than $10,000 over a 30-year period. |

$100 at 2% interest | |

| Year 1: | $102.02 | |

| Year 5: | $110.51 | |

| Year 10: | $122.12 | |

| Year 20: | $149.13 | |

| Year 30: | $182.12 | |

| Add $20 per month | ||

| Year 1: | $344.63 | |

| Year 5: | $1,373.56 | |

| Year 10: | $2,780.94 | |

| Year 20: | $6,054.90 | |

| Year 30: | $10,053.05 | |

It’s important to make frequent, regular deposits. If your 14-year-old begins to deposit $20 in babysitting earnings every week in a savings account that pays 1%-2% interest, by the time your child enters college the account should be worth about $5,400. On the other hand, if your child deposits only $20 per month for the same period, the account would be worth about $1,250.

Anti-fraud alert

There are many ways to lose money to crimes and fraud. Discuss the importance of safeguarding personal and financial information with your kids:

- Commit PIN numbers and passwords to memory—don’t write them down.

- Watch your surroundings when you withdraw money from an ATM.

- Be cautious about giving out your Social Security number—it can be used by an imposter to get credit in your name.

- Shred credit card solicitations, bills, old checks and bank statements before throwing them away.

- Don’t give out your bank information to salespeople who call on the phone—they could be scam artists.

- Don’t leave outgoing mail containing checks and other personal information in unlocked mail boxes or where strangers can pick it up.

- If you lose your ATM, debit or credit card, contact your bank immediately.

Credit cards

Credit where credit’s due

Good credit is important in obtaining a favorable interest rate on a car loan or home mortgage, renting a place to live, paying competitive car insurance premiums, getting homeowners’ or life insurance and applying for many kinds of jobs.

| To familiarize your kids with the concept of credit, go over your credit card statement with them. They’re probably used to seeing you pull out your card to pay, but have they ever looked at the statement’s bottom line or watched you write a check to pay the bill? Concepts like paying with plastic can be abstract without a reality check. |

The fine print |

| Teach your kids to read the fine print on credit card offers. The all-important details about interest rates, late fees and how much cash advances cost can all be found there. |

It’s a good idea for college-age children to have one credit card—this can help them build a good credit history. Ask them to give you the account number to keep tabs on the account so that you can head off any trouble. You will have more control over the card if you make them an authorized user on your credit card, and in most cases this will still help them build a credit history.

The Credit Card Accountability, Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009 (the CARD Act) requires that young people under age 21 show that they have the “ability to repay” before they can get a credit card. If your child doesn’t have a job or other income, you (or another responsible adult) will need to cosign in order to open a credit card account. Ask your child to give you the account number to keep tabs on the account so that you can head off any trouble. (As the co-signer on a card for a person under 21, you must be notified before the credit limit can be raised.)

College credit |

Students and credit cards |

| Three quarters of college students have at least one credit card. Some kids see credit cards as free money and use the card until it’s maxed out. Failure to manage their first credit card accounts has caused many students to endure years of damaged credit or even bankruptcy. With credit cards, looks can be deceiving. Just because a card has a cool appearance or a flashy photo, or is issued by your kid’s school or favorite sports team, does not mean it’s a good deal. Teach your kids to compare several cards to find one with really important characteristics: a low interest rate, low or no annual fee and lower-than-average late fees. To avoid over-limit fees, advise them not to let the card company approve charges above the credit limit. The CARD Act, in addition to making sure that your child has the ability to repay any line of credit extended by a credit card company, also restricts credit card marketing on campus and prohibits giving gifts (such as t-shirts, caps and gift certificates) to students who apply for credit cards. Colleges are required to publicly disclose marketing agreements for school-branded credit cards. |

You can help your college-age children use credit cards wisely. Before your child leaves for college, agree on some basic groundrules, such as these:

|

Credit Reports

Pay on time

Penalties for late payments and interest charges on credit cards can add up fast. Make sure your kids know that they have to pay credit card and other bills by the due date. Most lenders charge late fees that can be as high as $39 if the payment isn’t there on time. Payments that are late by more than 30 days are reported to credit reporting bureaus. The black mark caused by the late payment stays on your credit report for seven years.

Pay more than the minimum

Most credit cards require cardholders to pay a monthly minimum payment of about 3% of the outstanding balance. Paying just the minimum will cost you a lot more in interest and keep you in debt much longer.

If your child has an average credit card balance of $1,000 at 17% interest and pays only a 3% minimum payment each month, it would take more than nine years to pay the debt. The interest alone could add more than $700 to the balance.

On the other hand, if your child makes a fixed payment of $100 each month, the debt would be paid off in 11 months with $86 in interest.

Bad credit is bad news

Graduating college with bad credit impacts more than just the ability to get loans or credit cards. The information in credit reports can be used by employers to screen applicants. In certain fields—financial services, technology and law enforcement, to name a few—credit checks for job applicants are the norm. No matter how good your grade point average was, or which degrees you’ve earned, bad credit can cost you the job.

People with bad credit usually have to put down cash deposits in order to get phone and utility service, which can add to the cost of establishing a residence.

Checking your credit

Make sure your kids know that they can check the credit information that is on file about them at the three major national credit reporting bureaus. Each year, you may request a free report from each of the three major credit reporting companies. (See “Annual Credit Reports” below for contact information.) Everyone who has had a credit card or a loan will have a record with one or all of these companies. First obtaining these reports when your child is around 16 allows you to check for identity theft and make corrections before your son or daughter needs to apply for a student or auto loan, apartment or job.

People who are turned down for credit can get a free copy of their credit report from the company that supplied the information, or you can buy a copy anytime for about $10-$15, depending on the company.

Annual Credit Reports

Online: Annual Credit Report

By phone: 877-322-8228

By mail: Print out the order form from the web site and mail it to the address provided on the form.

Driving

Gotta have wheels

When it comes to cars, many kids focus on the monthly loan payment—but ownership costs can more than double that figure. (See “Monthly Cost of Owning a Car”.) Running through some of the costs of auto ownership with your child is an important reality check.

You want your children to have a safe vehicle, but with new car prices so high a used vehicle is a more likely choice. A new car will lose 20%-40% of its value in its first year.

Many dealers now sell “certified pre-owned” cars—late model trade-ins and lease-end cars that have been thoroughly inspected and come with warranties and extended protection plans. But when buying any used car, even certified pre-owned vehicles, do your homework and get an independent mechanic to check the car. New and used car values as well as car-buying tips can be found online at the Kelley Blue Book site (www.kbb.com). For a small fee, you can learn the car’s history by checking its vehicle identification number (VIN) at CarFax (www.carfax.com).

Auto insurance—ouch!

The cost of auto insurance for young drivers can give you sticker shock. According to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, for each mile driven, the risk of being involved in a crash is four times higher for teens aged 16-19 than for older drivers. Drivers who are 16 present the highest risk, with a crash rate almost three times that of 18-year-olds. These statistics give insurance underwriters a reason to charge the highest premiums for young drivers.

Teenaged girls are not considered as high-risk insurance-wise as teenaged boys and generally qualify for lower insurance rates.

The insurance industry offers these tips for covering your young driver for the least expense:

- “Safe” cars can be less expensive to insure. SUVs, for instance, have a history of rollovers, which can result in higher premiums. The safest cars—find a list at SaferCar.gov—are not going to make your teen the center of attention in the school parking lot, but they should be somewhat cheaper to insure.

- If your teen has a B average or better in school, you might get a small discount for good grades.

- Adding your teen driver to your own policy might cut costs if you qualify for good-driver discounts. This can also qualify you for multiple car discounts. This doesn’t mean you have to pick up the whole tab—you can pro-rate the premium and ask your child to pick up his or her share.

- Encourage your teen to take driver safety classes that result in eligibility for insurance company discounts.

- When purchasing auto insurance (or any other insurance) shop around among companies to compare premiums and consider higher deductibles. The more you are willing to pay out of pocket for claims, the lower your premiums will be.

- Make sure you explain that speeding tickets and other moving violations and accidents (even fender benders) can cause your insurance costs to soar. Discuss the serious consequences of drunk driving. Emphasize that if your teen doesn’t drive safely, he or she might not be able to drive at all because of the prohibitive cost of auto insurance for drivers with a poor record. (Set a good example when you drive—actions can speak louder than words.)

Monthly Cost of Owning a Car

This chart estimates the approximate monthly cost of purchasing, financing and operating a $10,000 auto to be driven and insured by a 17-year-old male. In this example, the buyer makes a $2,000 down payment and finances the balance at 6% interest for 4 years.

| Annual expense | Monthly cost |

| Loan payment: $2,254.56 | $187.88 |

| Maintenance: $120 (4 oil changes) | $10.00 |

| Equipment: $200 (new tires) | $17.00 |

| Repairs: $100 (muffler) | $9.00 |

| Gas*: $1,632.00 | $136.00 |

| Insurance: $1,500 per year | $125.00 |

| Initial sales tax at 6%: $150 | $12.50 |

| Annual registration: $60 | $5.00 |

| Total : | $502.38 |

*12,000 miles, 25 miles per gallon, $3.40 per gallon.

Cell phones

Cutting the cord

Teenagers, known for their love of the phone, make up an important, fast-growing segment of the cell phone market. Many parents pay for cell phone service to keep track of their children and to make sure they can get help in an emergency.

Carriers have family plans and pre-paid accounts designed for the teenage market, but these might not offer the best deals. Family plans let you add multiple lines to one account and share the plan minutes between the phones.

Older teens usually want a personal cell phone—but because they don’t have a credit history, you might be asked to co-sign. While it will take some doing to distract your teen from the phone’s color or ring, you might fend off hundreds of dollars in extra charges by exploring prepaid cell phone plans.

- Most wireless plans charge for minutes when you make and receive calls. Often, family plan users are not charged when calling each other’s phones.

- On a cell phone, even toll-free numbers cost money.

- The charges for directory assistance and connecting calls can be surprisingly high. If you have a Web-enabled phone, you can avoid those costs by looking up contact information on the Internet.

- Prepaid cell phones are worth a look because the monthly charges have dropped drastically and the plans require no credit checks. Many prepaid cell phones have plans that include unlimited texting and data downloads.

- Custom ring tones, voice mail and other optional services usually result in additional charges.

For more information

Web sites worth checking out

Burning questions: Kiplinger's online archive of "Money Smart Kids" columns (/www.kiplinger.com/fronts/archive/column/index.html?column_id=2) contains dozens of articles of interest to parents looking to give their kids solid money advice.

Fun finance: The Motley Fool's “Teens and Their Money” (www.fool.com) presents the novel viewpoint that it’s fun to learn how to save, earn and invest money.

Reality check: Jump$tart’s web site (www.jumpstart.org) is full of guidance and tips on money—all of it geared to teaching young people. The “Reality Check” interactive quiz helps teens learn what it costs to live on their own.

Be your own boss: YoungBiz (youngbiz.com) features stories about teen entrepreneurs who’ve started “fresh, funky and financially rewarding” businesses.

Money can’t buy everything: The Center for a New American Dream (www.newdream.org) promotes responsible consumption with the goals of protecting the environment, enhancing quality of life and promoting social justice.

Advice is nice:Family.com (http://www.family.go.com/parenting/pkg-teen) offers all kinds of parenting advice and strategies focusing on the teen years.

Snag a job: You don’t have to be an adult to use the Internet to conduct a job search. Check out sites geared especially to teens www.teens4hire.com, www.snagajob.com), as well as the big job sites like Monster.com and those of national retail and food service chains.

Where’s the money? FinAid (www.finaid.org) is a trustworthy site packed with “how to” guidance on getting student financial aid.

Test this: Surf over to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (www.sec.gov/investor/tools/quiz.htm) and “Test Your Money $marts” with its challenging interactive quiz.

Published / Reviewed Date

Reviewed: October 22, 2019

Download File

Teens & Money - Talking to teens about money (English)

File Name: Teens_And_Money_2013_EN.pdf

File Size: 0.3MB

Sponsors

Filed Under

Copyright

© 2003 –2024 Consumer Action. Rights Reserved.